| Willingness to Meet Demand |

- From a strategic point of view, this involves deciding on whether production will be centred on the maximum compliance with individual demands or on the contrary, influencing these demands

(Keřkovský, Valsa, 2012). In the first case, production must be capable of producing the given product based on the specific needs of the customer, which in turn corresponds with the production system (produce to order). In the second case, products are more standardized and production is based on the produce to stock system. Assemble to order is also a commonly used strategy.

- Produce-to-order strategies are implemented based on customers’ individual orders, allowing for the maximum customization of features and product delivery times based on the customers’ demands. The downside is that customers must accept that such a production system is more time-consuming and is generally more expensive than a produce–to-stock strategy. In terms of production and strategy, producing to order resembles the conditions for piece and small batch production and differentiation strategies. It also requires a steady flow of orders, which is dependent on effective and reliable marketing and sales strategies.

- The produce-to-stock strategy involves shipping finished goods to the warehouse from where they are later distributed to customers. The produce-to-stock approach is suitable for sectors with generally predictable demand. This approach caters to customers who require speedy delivery of generic products, that is to say, it is not suitable for customers who require customized products, due to the high cost of storing such a wide range of products. In terms of production and strategy, this approach resembles conditions for serial and mass production, monitoring cost strategy, allowing for better planning conditions, smooth large-scale production, leading to economies of scale, which should outweigh storage costs (Žufan, 2011a).

- Assemble to order involves the production of products that address customer demands, albeit to a limited degree, due to the standard parts that are used. Assemble to order can then be seen as a combination of the two aforementioned methods. It is a modern concept, applied primarily in the automotive industry, construction and other industry sectors.

|

| Production Planning and Management |

- Deciding on the production concept and whether it will be based on a push or pull strategy (adapted from Keřkovský, Valsa, 2012):

- Push Strategy – usually based on Material Requirements Planning, or MRP. The point of departure for such a strategy is forecasting inventory demand, on the basis of which inputs are ordered and prepared and thereby pushed onto the consumer. One of the basic tools employed for push strategies is a Bill of Materials, or BOM, which covers all of the parts required to manufacture an end product. The predicted amount is then, on the basis of the BOM, projected onto purchase volumes, input preparation and subsequent production plan (Žufan, 2011b). Alternatively, an MRP II (Manufacturing resource planning) strategy can be employed, which involves other aspects of production management, such as workshop planning, monitoring cash flow, planning business activities, CRP, or Capacity Requirements Planning, and others. Apart from the capacity planning of the entire production capacity, requirements for machinery capacity, human resources and others, this strategy can also enable the monitoring of production time flow and individual activities, allowing for the planning and scheduling of production (Košturiak, J., Gregor, M., 1993). A disadvantage of this strategy is its rigidity and inability to quickly react to developments in customer demands.

- Pull Strategy – is based on “waiting for the customer’s order to be made.” This strategy stems from inventory demand forecasts, which are only projected onto the capacity requirements planning process. It is not until a customer makes an order that system activity is triggered. Only then does gradual “counter” communication come into play, so that individual manufacturing or processing measures can be taken in direct response to individual orders, allowing the order to be successfully finalized as quickly as possible. Among the “pull” production strategies are Just-in-time, KANBAN, Optimized Production Technology, or OPT and the Theory of Constraints, or TOC (Žufan, 2011b, Košturiak, Gregor, 1993). An advantage of the pull strategy is the generally lower cost of production as a result of lower safety stock volumes and production time. The pull strategy concept is subject to the interest of buyers, as well as the production of appealing, quality products. The company’s success is then dependent on continuous innovation and developments of new products (Keřkovský, Valsa, 2012).

Just-in-time (JIT)

The aim of the Just-in-time strategy, developed by the Japanese company, Toyota, is to manufacture the required volume of products in the required quality and time-frame without producing excess waste, by reducing machinery change-over times, reducing inventory, reducing shopping and handling times, and eliminating wasted time (Košturiak, Gregor, 1993). The concept of JIT is geared towards reducing all activities that do not actively contribute to creating product value. A disadvantage of this strategy is difficulty communicating with suppliers as well as internal communication and transport difficulties, amongst others. Disadvantages can be efficiently eliminated by implementing an adequate information system.

KANBAN

The basis of the KANBAN method (“signboard” or “billboard” in Japanese), is dividing the workplace into “suppliers” and “buyers,” where the supplier is also the buyer and neither is allowed to stockpile, requiring them to deliver precise quantities on time, which automatically leads to the reduction of time wasted by mutual checking. Communication in the workplace is carried out via cards (Kanban), where the buyer places an order with the supplier by sending him an “order” card, and the supplier, who is also the manufacturer of the required parts, delivers the required quantity of goods within the necessary time-frame with the delivery notice, that is, with a “delivery notice” card (Košturiak, Gregor, 1993). The KANBAN method, by way of monitoring and regulating the number of cards in the operational system, enables the control and management of the entire production process.

Theory of Constraints

Management strategies using the theory of constraints, or theory of bottlenecks, are based on balancing production flow, not capacities, and employing a system that is limited by at least one constraint. This is a rather unconventional approach (Basl, Šmíra, 2003), that stems from the notion that an attempt to utilize workplace capacities to their full potential does not always lead to the maximum utilization of the entire system. It requires realizing that hours wasted in a bottleneck workplace are hours wasted for the entire system, and vice versa – time saved with non-bottleneck machinery is merely an illusion and does not have any effect on the entire system. In this manner, bottleneck, or “low profile workplaces,” impact not only production times but also quantities. There is a distinction to be made between local insight (insight into the capacity of a given workplace) and global insight (insight into capacity options of the system-wide chain of workplaces). Implementing a theory of constraints philosophy is carried out in five steps (Stevenson, 2005): identifying the system constraints, maximum exploitation of the system constraints, subordinating all activities to the system of constraints, eliminating the constraint and returning to the first step, i.e. re-identifying system constraints, as expanding one system constraint may lead to the development of another constraint.

- An important aspect which should be included in the production strategy is ensuring production stability (ability to recover from, for example, machinery and equipment outages, human error, delivery failures, unforeseen fluctuations in demand, natural disasters.) Possible corrective measures can be, for example, sufficient quantities of raw material reserves, strategic alliances in the event of a crisis, diversification, insurance and others

(adapted from Keřkovský, Valsa, 2012).

- In terms of the production strategy, aspects that should be addressed include: ethical, ecological, hygienic, or other aspects (text below adapted from Keřkovský, Valsa, 2012)

- product (health and safety of the customer, recyclability of used products, energy consumption),

- deployment of production (employment, impact on the environment and business environment),

- arrangement of workplaces (safety and hygiene regulations and aspects, employment of impaired workers),

- environment impact of production plant (safety and hygiene regulations, safe handling of hazardous materials and waste, not disturbing the surroundings with noise or emissions),

- production organization and planning (extensity and intensity of work in terms of hygienic regulations and standards, employees must be given sufficient rest time between shifts etc.).

|

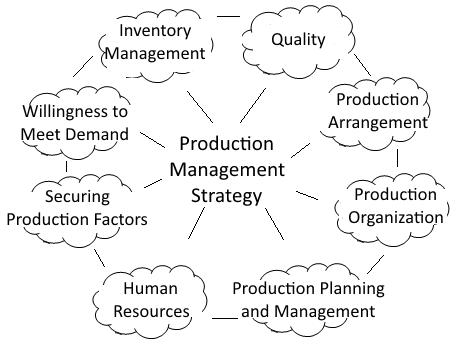

Production Management Strategy (Keřkovský, 2009, Keřkovský, Valsa, 2012), authors’ own processing

Production Management Strategy (Keřkovský, 2009, Keřkovský, Valsa, 2012), authors’ own processing